Keep Cool Stay Warm

I am going to write down four words in a second, and if they register as familiar to you then you are of a certain age. You will be somebody who taped the Top 40 on a Sunday night, you will have at some stage attempted to reconstitute a “Vesta” dried Chinese meal, and you will only ever describe carpet deodorant as “Shake N Vac”. Here we go:

“Central heating for kids…”

Back in 1976 it was common place to feed your children with a powdered food source that resulted in them developing a striking and shimmering total body glow. Nobody panicked about this, or even commented upon it… least of all the children themselves who found themselves lit up as if they had ingested a few kilos of weapons grade plutonium. Remarkably you can still buy this product today, but the luminescent additives seem to have been removed. Here’s a TV advert for it back in the day:

While we are on the subject of body temperature I have just read an article by a well known online running magazine that had me hot under the collar in no time. It’s December, and they have to write about something, so they had re-cycled the old “advice in cold weather” chestnut. However this time they were going for another angle… they were pointing out why your performances and times will drop off in cold weather, and selling you the idea that for this reason the winter months are best used for base line lower intensity training, and not a time to chase your numbers. I was almost buying into it until they started to reel off some pseudo-physiology… then I came to my senses and realised this was typical running industry conk.

It was one sentence that really did it for me. They were suggesting that you will have less lead in your running pencil because: “Your fast twitch muscle fibres will be adversely affected as cold muscles have a reduced ability to generate force”. There is a fundamental problem with this statement when it is taken in the context it was being used. It’s nonsense.

Here’s why. Right now, if you are free from illness, and are comfortable enough to be reading this, then you (that’s your body) will be running at 98 degrees Fahrenheit, give or take a degree, or 37 degrees Celsius, give or take half a degree. If you don’t believe me go grab a glass thermometer, some lubricant, and lock the door. It’s intimate, but it’s accurate. In fact one of my favourite bits of research cheekiness relates to it. In 2015 the University of Calgary produced an exhaustive 24 page study on the best form of temperature taking in The Annals of Internal Medicine (that’s one letter away from a cheap joke already). The researchers concluded that rectal thermometry was significantly more accurate when compared to oral, armpit or auricular methods. Within the papers conclusion the researchers slipped in that rectal thermometry was indeed, and I quote, “the bottom line”.

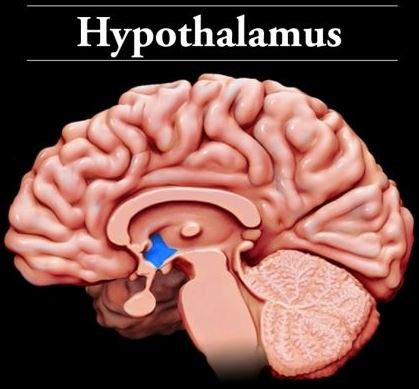

Back to the cold muscle having reduced abilities. It hasn’t, because it isn’t cold. Mainly because you have one of these:

It’s a tiddly little area of brain that hangs out next to your pituitary gland. It doesn’t store thoughts, or motor programs, or convert images, or moderate speech, or dream. It’s job is to be a homeostat, or lets call it a thermostat. It keeps things ticking along nicely, especially your body temperature, which it keeps pretty constant according to what you are doing. A mesh work of receptors throughout the body feed input into it. Your hypothalamus processes this and produces instructions via it’s neural output that open and close blood vessels, control arterial flow, venous return, blood pressure, sorts out your sweating levels, influences your thirst, and slams on the hormonal brakes if you are under, or over cooked. It’s proper handy. It keeps you at an optimum temperature… all of you, including any muscly bits. It may be cloudy with a chance of showers outside, but inside it is a constant 37 degrees. These cold muscles, that aren’t actually cold anyway, will soon get warm even though they are warm already… or rather “just right”. That’s how the hypothalamus thinks (which I don’t think it can, but who knows cos it’s in your brain where all the thinking is going on). It keeps things “just right”. Anyways, if you do go for a run, it really doesn’t matter if it’s arctic or tropical out there, because not far into the run your busy muscle groups are going to shift into aerobic energy system mode and demand an increased blood supply. Your hypothalmus, and it’s glandular companions, will oblige by turning on the taps. Nice toasty oxygen rich blood. Furthermore, running is a total body exercise with multiple muscle groups involved. Are they all cold, or are just the calves cold, or is just one leg cold?

There is another thing with body temperature that any runner will be well aware of. Take a look at these two pictures of a group of athletes on a training run in the city two days before the Pittsburgh Cross Country Championships 2018. The second is on race day itself where the snow had melted but it was still mighty cold. Spot the difference?

Body temperature has a relationship with intensity… but don’t go thinking it goes up because you are running at high intensity… it only does that if you make the mistake of letting it. In both pictures I would bet that the runners core temps, or even calf muscle temps, are similar and within a safe threshold. To help them achieve that on the high intensity and high effort race day they employ a cunning strategy… strip off. Their internal central heating is on boost mode and has completely over-ridden any external influence of the weather. And trust me, their muscles are producing plenty of force.

The online article got itself all confused about sweating as well. Apparently, in cold weather you are less likely to sweat, which can create something called a “hydration imbalance”, and make it difficult for you to control your body temperature. I honestly think that these articles are written by folks who don’t own a pair of trainers… or Prince Andrew. Go overambitious with your layers on a cold day, and go out for a hard run and boy will you sweat. Soaked. Not only that but the sweats main job of employing the latent heat of evaporation to effectively cool down surface temperature will be lost under the layers… and you’ll get double hot. I didn’t understand the hydration imbalance thing and it was clear they didn’t either. Further on in the article they rattled on about decreased heart rates, cardiac output and respiratory distress. These are physiological effects of hypothermia and they will certainly decrease your running performance, but if things get to that state you almost certainly won’t be running anyway.

Anyway, enough of the criticism as I want to pitch in with some of my own advice for cold weather running. Some of this will be familiar to you, but it’s always worth reviewing, and I like to think it is more useful than non-scientific scaremongering.

You can run fast when it’s cold. Really fast. Like beat your Park Run/CC 10k PB fast. Folks will be doing it this weekend.

The winter months may indeed be an opportunity to work on your base line low intensity training. I think of it as preparing those long term adaptations to your aerobic capacity and threshold, but not thrashing the body into recovery “catch up”. Slow and regular, slow and long. It is more of a year long periodisation thing rather than a winter weather thing… your events tend to be in the warmer months so it just fits. Of course if you have a winter season on the fells or trails… you’ll be on it.

Lets think of the three main “paces” in your winter training and cross reference them with clothing. On the one end you have those low intensity, slow, easy, but perhaps long runs. On the other end you have high intensity race or event efforts. Then in the middle you have the awkward one… a quicker, higher quality, tempo training run, shorter but sharper, and more difficult to get the layers right!

For the low intensity runs go for the 3 layer principle. Next to the skin a decent quality “wicking” layer which disperses rather than absorbs perspiration. Not an easy job, and many of the specialist layers don’t live up to their reputations! The mid layer is your insulator and should be able to “trap” air but be breathable (a paradox). Basically it needs some space between its fibres, so steer away from the dense cottons and synthetics but pick a material with some “loft”. Some folks swear by old school merino wool, others favour the modern micro-fibres. The outer layer serves as double-duty by being breathable but water resistant, and of course wind resistant. It will probably cost you, and look after it… air dry as soon as you can, and never scrunch and forget in your car boot. It’s always going to be personal preference but on these runs if you are getting too warm, slow down, because you are probably going too fast anyway. Hat and gloves… your choice.

For race day I am hoping you are going to hit the line hot with a decent warm up, and then be pushing along at threshold. You should be hot. Temperature issues will come after the race. Your running muscles (lets say limbs) will be pumped up and hot with the hypothalamus shunting blood/temp from core to periphery. It takes a while to balance out as that increased peripheral blood flow is aiding the physiological recovery within your muscles immediately after your run. The core temp may indeed see a relative drop, and you’ll feel that, you may get the shivers at the medal ceremony. Prepare… get your dry and lofted layers ready at the finish line. Get your club vest off as soon as possible, even your shorts and socks. Put on air trapping lofted layers, and over do it. You may still be sweating and generating peripheral heat, but your core temp may have fallen.

That mid range tempo run is tricky. Triple layer it and you might cook up. Strip off and you could get cold quick, especially if conditions change. I think it is all about your warm up to get this right. You need a removable outer layer/layers over your “at temperature” choice. Don’t run the loop from home throwing layers into hedges. Get that over and done with in your warm up. Walk out for say 600m hard, jog back home, go past if you have to and back, get up to temp discarding one layer at a time back home. Once the balance is right hit your watch button and off you go.

Occasionally you are going to get it wrong, or conditions will change and you are going to get cold. Best advice is to get back to your home, base, car by the shortest route, and if at all possible with a slight lift in intensity. But do not go crazy and hit your fatigue threshold… cold and fatigue are a bad mix. DO NOT stick to your planned programme session if you are cold for fear that you are not achieving your training goals. Be smarter than that. Bale.

Interval training can be awkward in cold and damp weather. A period of sweating, followed by a period of sweat absorption (you get damp real quick on a hard interval session). A period of high oxygen demand, followed by recovery from oxygen debt. The hypothalamus gets proper busy. Core temperature can fluctuate. If you are repping in one place then take along some extra and alternative layers to swap out during the session. These are often group sessions so if you travel to them by car make sure you have a thick, lofted and dry layer waiting for you in the motor for the trip home. While we are on the subject of your car, it is highly recommended that you search out some “past it’s sell by date” layers, seal them up nice and tight and waterproof, now hide them in your Allegro. Emergency layers, always there if you need them, but folks just don’t do it… go do it right now!

I know this is very simple advice, but simple preparation always works best. You can trust your hypothalamus to get it right most of the time, but if all else fails then I could mix you up some of my special breakfast cereal.

Comments are closed.